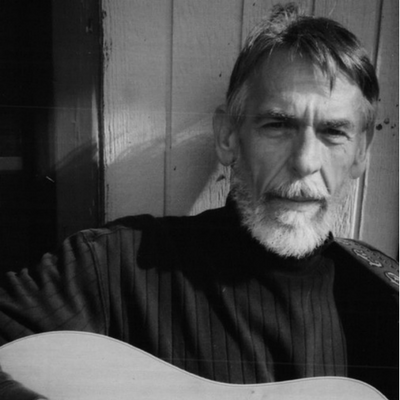

Billy Wagoner

Musician, Preservationist, Music Historian & Journalist

As read by Jai Templeton, Tennessee Commissioner of Agriculture

June 9, 2017

Billy Wagoner will tell you that he’s no professional musician, that music is just a hobby for him. He’ll tell you that his long association with some of this region’s finest musicians happened quite by accident one day when he walked into Wayne Jerrolds’s music store in Savannah, Tennessee. If you press him a little harder, he’ll admit that it was all in the Divine plan, that his life panned out just as it did because God placed all those musicians and opportunities in his path. That’s probably closer to the truth.

Bill, with characteristic humility, sells his musical ability short. He is more than a little handy with a number of stringed instruments, including banjo and guitar, and we’ve got the recordings to prove it. But he is probably right that making music was never his primary calling. His greatest gift, the one that has earned him our enduring respect and admiration, the one that we recognize here tonight, is his role as a teller of stories. If McNairy County has a sage of local history and musical heritage, it is unquestionably Billy Wagoner.

Bill’s lifelong affinity for music began when he was no more than knee-high. Among his first memories are dancing until he dropped (literally), to the mesmerizing sounds of the old-time reels, breakdowns, and hornpipes at one room school houses and private homes around his native Stantonville, Tennessee. It was in these informal performance venues that he first became intimately familiar with the styles and repertoires of local masters like Ocie Humphrey, Con Crotts, and Hall of Famers such as the great Elvis Black. Like everyone else, Bill and his family were there to enjoy the music and dancing, but his keen powers of observation were already at work. He was paying attention.

As the young man’s interest in music grew, he would become a proficient musician, befriending and joining many of his musical friends and mentors in recording and making live music in every possible venue in West Tennessee and beyond. For many years he fronted his own band, Flatwoods Bluegrass, with popular regional success. If you have the chance, just ask him about his many years of experience and who he’s had the opportunity to play with, over the years, but set aside a little time. You’ll need it, but it will be well worth it. I don’t think Bill would mind me saying, of all the renowned musicians He’s shared the stage with, he reveres no one more than two of his friends and musical collaborators, Wayne Jerrolds and David Killingsworth, who are on hand to play a musical tribute for Bill’s induction tonight.

When Bill wasn’t making it, he was organizing and creating opportunities for others to showcase their music. For many years, he was the primary music coordinator for the Buford Pusser Festival, among other events, using his lengthy list of contacts to bring high quality local and regional talent to the stage, exposing thousands of annual visitors to the bluegrass and old-time music he grew up on and so loved. He was, in fact, so successful at tapping into the regional appetite for traditional music that it virtually demanded he do something on a more regular basis. In 1997 he joined an existing effort to promote live local music in his hometown by taking over management of the Adamsville Bluegrass Jamboree. It is no exaggeration to say that you would have been hard pressed, in those days, to find a better traditional music event anywhere in the state of Tennessee. On any given Jamboree Saturday you could reasonably expect to find some of the finest talent in the tristate area performing at the Adamsville Community Center—now known as the Marty—for very appreciate and enthusiastic regional audiences. Just as important, was the opportunity it gave local pickers to cut their teeth as performers and hone their skills as musicians, not to mention getting rubbed with a little bit of that green salve. The impact of the Jamboree on the local culture and economy is inestimable. The role of cultural ambassador suited Bill well.

Even so, I don’t think anyone would argue that Billy’s singular contribution to our shared musical heritage has been in the realms of music preservation and journalism. In the 1980s Billy was instrumental in creating awareness about a nearly forgotten archive of old acetate records that sat deteriorating in an Eastview closet. Most people would have thought nothing of it, but when Billy Wagoner learned that David Killingsworth was making cassette transfers from the acetate collection of Stanton Littlejohn, he convinced David to make him copies and even add a little commentary about the artists who had mentored him as a young musician. Bill immediately recognized the importance of these tracks and was the first to broadcast them over the airwaves on a radio program sponsored by the McNairy County Historical Society. This conscious act of promoting the value of local music was responsible, in part, for the rediscovery and preservation of these rare cultural artifacts by Arts in McNairy’s traditional arts team. The Littlejohn Collection is precious beyond measure and its significance has now been recognized by the Tennessee Arts Commission, the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University, and the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, who have all invested heavily in its preservation. Bill knew it all along.

If you grew up near Adamsville, Tennessee or one of the other small communities in Eastern McNairy County, your home was probably never without the latest edition of the local paper, the Community News. The Community News was everyone’s primary source for local information and it was most often delivered to your home, with a warm greeting, by a trusted friend. Bill was the publisher, editor, writer, photographer, ad sales department, layout and design artist, distributor, janitor, repairman, chief cook and bottle washer at the Community News for every year of it’s existence. I am pretty sure, Mrs. Bobbie often wore more than than a few of those hats since it was a family business in the truest sense of the word, but their was no doubt that Bill maintained editorial control, and so got to write about whatever he wanted.

Through his Wagon Spokes column, Billy consistently shared interesting tidbits of local history each week accompanied by his characteristic wit and wisdom. It was always fascinating, always informative, and always eagerly anticipated by every regular reader. As often as not, the column seemed to feature the story of a noted musician, or some local music tradition. Over the years, Bill ran articles about Elvis Black, Pap Whitten, Waldo Davis, Dewey Phillips, Arnold English and the Dixie Hayriders, Carl Perkins, the Murray Brothers, The Whitten Brothers, Con Crotts, Wayne Jerrolds, The Holland Family, Merle “Red” Taylor, Eddy Arnold, Kay and Buddy Bain, Eddie Bond, Bo Jack Killingsworth, and many others. He wrote about the old-time home musicals and barn dance traditions, and the provenance and current whereabouts of famous local fiddles. He wrote about sacred music, Southern gospel, and the shape note singing tradition. He wrote about the Stanton Littlejohn recording sessions and Earl Latta’s old-time music jams held in this very building. He wrote about Johnny Cash performing at Stantonville and Elvis Presley appearing at Bethel Springs, before those were household names. Often, the period photos he dug up to illustrate these articles were as valuable as the narrative he so capably supplied. Bill also used valuable ad space in his paper to promote every kind of music event in the region. And that’s just scratching the surface. If there was a musical story to be told, Billy told it. It’s fair to say that Billy provided the first written record, of many local music traditions that might easily have been forgotten had he not called attention to them. If all those Wagon Spokes stories could be collected into one volume, what a treasure that would be.

It’s important to say that we are not just speaking in the past tense when we talk about Bill’s contribution. At 80 years old, he’s still playing music, as you will soon see, and he still writes the occasional guest column for the McNairy County News and Independent Appeal. You can bet, if there is good story to be told or a good tune to be played, Bill will be there.

If he is right that God placed all those great musicians in his path, and provided all those opportunities for him to share the stories of our musical heritage—and I have no doubt he is—then it only stands to reason that God sent us Billy Wagoner. For six decades Bill has served as a constant reminder that McNairy County has an unparalleled cultural heritage well worth preserving, worth crowing about, and worth passing on to the next generation. His spirit of optimism and unflinching faith in the power of music as a force for good in our communities and individual lives has taught and inspired us all. Just as importantly, Bill has given us an authoritative written record of our history and cultural heritage that will be consulted and valued long after we are all gone. Now that’s an accomplishment worthy of the highest praise and recognition.

It is my distinct honor to Induct Billy Wagoner into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in the class of 2017.

June 9, 2017

Billy Wagoner will tell you that he’s no professional musician, that music is just a hobby for him. He’ll tell you that his long association with some of this region’s finest musicians happened quite by accident one day when he walked into Wayne Jerrolds’s music store in Savannah, Tennessee. If you press him a little harder, he’ll admit that it was all in the Divine plan, that his life panned out just as it did because God placed all those musicians and opportunities in his path. That’s probably closer to the truth.

Bill, with characteristic humility, sells his musical ability short. He is more than a little handy with a number of stringed instruments, including banjo and guitar, and we’ve got the recordings to prove it. But he is probably right that making music was never his primary calling. His greatest gift, the one that has earned him our enduring respect and admiration, the one that we recognize here tonight, is his role as a teller of stories. If McNairy County has a sage of local history and musical heritage, it is unquestionably Billy Wagoner.

Bill’s lifelong affinity for music began when he was no more than knee-high. Among his first memories are dancing until he dropped (literally), to the mesmerizing sounds of the old-time reels, breakdowns, and hornpipes at one room school houses and private homes around his native Stantonville, Tennessee. It was in these informal performance venues that he first became intimately familiar with the styles and repertoires of local masters like Ocie Humphrey, Con Crotts, and Hall of Famers such as the great Elvis Black. Like everyone else, Bill and his family were there to enjoy the music and dancing, but his keen powers of observation were already at work. He was paying attention.

As the young man’s interest in music grew, he would become a proficient musician, befriending and joining many of his musical friends and mentors in recording and making live music in every possible venue in West Tennessee and beyond. For many years he fronted his own band, Flatwoods Bluegrass, with popular regional success. If you have the chance, just ask him about his many years of experience and who he’s had the opportunity to play with, over the years, but set aside a little time. You’ll need it, but it will be well worth it. I don’t think Bill would mind me saying, of all the renowned musicians He’s shared the stage with, he reveres no one more than two of his friends and musical collaborators, Wayne Jerrolds and David Killingsworth, who are on hand to play a musical tribute for Bill’s induction tonight.

When Bill wasn’t making it, he was organizing and creating opportunities for others to showcase their music. For many years, he was the primary music coordinator for the Buford Pusser Festival, among other events, using his lengthy list of contacts to bring high quality local and regional talent to the stage, exposing thousands of annual visitors to the bluegrass and old-time music he grew up on and so loved. He was, in fact, so successful at tapping into the regional appetite for traditional music that it virtually demanded he do something on a more regular basis. In 1997 he joined an existing effort to promote live local music in his hometown by taking over management of the Adamsville Bluegrass Jamboree. It is no exaggeration to say that you would have been hard pressed, in those days, to find a better traditional music event anywhere in the state of Tennessee. On any given Jamboree Saturday you could reasonably expect to find some of the finest talent in the tristate area performing at the Adamsville Community Center—now known as the Marty—for very appreciate and enthusiastic regional audiences. Just as important, was the opportunity it gave local pickers to cut their teeth as performers and hone their skills as musicians, not to mention getting rubbed with a little bit of that green salve. The impact of the Jamboree on the local culture and economy is inestimable. The role of cultural ambassador suited Bill well.

Even so, I don’t think anyone would argue that Billy’s singular contribution to our shared musical heritage has been in the realms of music preservation and journalism. In the 1980s Billy was instrumental in creating awareness about a nearly forgotten archive of old acetate records that sat deteriorating in an Eastview closet. Most people would have thought nothing of it, but when Billy Wagoner learned that David Killingsworth was making cassette transfers from the acetate collection of Stanton Littlejohn, he convinced David to make him copies and even add a little commentary about the artists who had mentored him as a young musician. Bill immediately recognized the importance of these tracks and was the first to broadcast them over the airwaves on a radio program sponsored by the McNairy County Historical Society. This conscious act of promoting the value of local music was responsible, in part, for the rediscovery and preservation of these rare cultural artifacts by Arts in McNairy’s traditional arts team. The Littlejohn Collection is precious beyond measure and its significance has now been recognized by the Tennessee Arts Commission, the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University, and the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, who have all invested heavily in its preservation. Bill knew it all along.

If you grew up near Adamsville, Tennessee or one of the other small communities in Eastern McNairy County, your home was probably never without the latest edition of the local paper, the Community News. The Community News was everyone’s primary source for local information and it was most often delivered to your home, with a warm greeting, by a trusted friend. Bill was the publisher, editor, writer, photographer, ad sales department, layout and design artist, distributor, janitor, repairman, chief cook and bottle washer at the Community News for every year of it’s existence. I am pretty sure, Mrs. Bobbie often wore more than than a few of those hats since it was a family business in the truest sense of the word, but their was no doubt that Bill maintained editorial control, and so got to write about whatever he wanted.

Through his Wagon Spokes column, Billy consistently shared interesting tidbits of local history each week accompanied by his characteristic wit and wisdom. It was always fascinating, always informative, and always eagerly anticipated by every regular reader. As often as not, the column seemed to feature the story of a noted musician, or some local music tradition. Over the years, Bill ran articles about Elvis Black, Pap Whitten, Waldo Davis, Dewey Phillips, Arnold English and the Dixie Hayriders, Carl Perkins, the Murray Brothers, The Whitten Brothers, Con Crotts, Wayne Jerrolds, The Holland Family, Merle “Red” Taylor, Eddy Arnold, Kay and Buddy Bain, Eddie Bond, Bo Jack Killingsworth, and many others. He wrote about the old-time home musicals and barn dance traditions, and the provenance and current whereabouts of famous local fiddles. He wrote about sacred music, Southern gospel, and the shape note singing tradition. He wrote about the Stanton Littlejohn recording sessions and Earl Latta’s old-time music jams held in this very building. He wrote about Johnny Cash performing at Stantonville and Elvis Presley appearing at Bethel Springs, before those were household names. Often, the period photos he dug up to illustrate these articles were as valuable as the narrative he so capably supplied. Bill also used valuable ad space in his paper to promote every kind of music event in the region. And that’s just scratching the surface. If there was a musical story to be told, Billy told it. It’s fair to say that Billy provided the first written record, of many local music traditions that might easily have been forgotten had he not called attention to them. If all those Wagon Spokes stories could be collected into one volume, what a treasure that would be.

It’s important to say that we are not just speaking in the past tense when we talk about Bill’s contribution. At 80 years old, he’s still playing music, as you will soon see, and he still writes the occasional guest column for the McNairy County News and Independent Appeal. You can bet, if there is good story to be told or a good tune to be played, Bill will be there.

If he is right that God placed all those great musicians in his path, and provided all those opportunities for him to share the stories of our musical heritage—and I have no doubt he is—then it only stands to reason that God sent us Billy Wagoner. For six decades Bill has served as a constant reminder that McNairy County has an unparalleled cultural heritage well worth preserving, worth crowing about, and worth passing on to the next generation. His spirit of optimism and unflinching faith in the power of music as a force for good in our communities and individual lives has taught and inspired us all. Just as importantly, Bill has given us an authoritative written record of our history and cultural heritage that will be consulted and valued long after we are all gone. Now that’s an accomplishment worthy of the highest praise and recognition.

It is my distinct honor to Induct Billy Wagoner into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in the class of 2017.

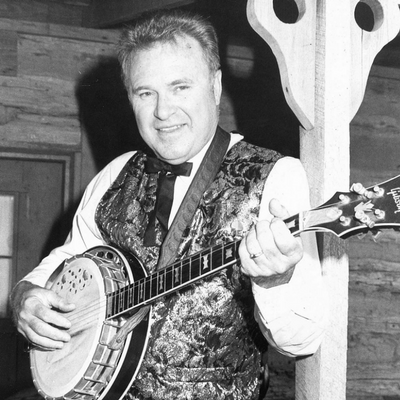

Carl Perkins

American Music Icon & King of Rockabilly

As read by Leanne Emmons, Arts in McNairy Music Committee Chair

June 9, 2017

It is hardly necessary to recite the many accomplishments of an artist such as Carl Perkins who is, without a doubt, one of the most revered figures in American music history. But in case you just arrived on the planet, we’ll bring you up to speed with the briefest overview.

Perkins is widely acknowledged as the “Father of Rockabilly Music” and an authentic cultural voice of the post-war South. His effortless mixing of honky-tonk country and R&B styles helped touch off a cultural revolution that gave birth to rock ’n’ roll, forever altering the course of American culture. The list of musicians and performers who cite Perkins as a primary influence reads like a who’s who of twentieth century rock music: Paul McCartney, George Harrison, John Fogerty, Rick Nelson, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Tom Petty, Paul Simon, Ronnie Hawkins, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the list goes on and on. Sir Paul McCartney famously said in one interview, “Without Carl Perkins, there would have been no Beatles.” The list of chart topping records, music industry awards, and international acknowledgments showered on Perkins are too numerous to mention. Suffice it to say he is a Grammy Award winner, a member of the Rock ’n’ Roll and Rockabilly Halls of Fame, and he is universally respected as an architect of contemporary popular music. His song, “Blue Suede Shoes,” is now one of the most familiar tunes ever written, as well as one of the most influential in American music history. The tune’s lasting impact has been acknowledged by inclusion in the Grammy Hall of Fame, the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry, and the Rolling Stone Magazine’s “Greatest Songs of All Times.” Perhaps under appreciated as a song writer, Perkins had five (FIVE!) compositions recorded by the Beatles, and many others by artists as diverse as Patsy Cline, George Thorogood, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, Jimmy Page, Dolly Parton, the Kentucky Headhunters, and the Judds. As a musician, Carl Perkins, along with contemporary artist and friend, Chuck Berry, virtually invented what would become the blueprint for rock ’n’ roll guitar—which is to say, the very sound of popular music for more than half a century now.

Here, in West Tennessee, Carl Perkins has achieved that rare status of a one-name-sensation like Cher, Madonna, or maybe more fitting for this occasion, Elvis. To us, he is just Carl. He is undisputed favorite native son of West Tennessee music. His name is synonymous with the regions incredible musical heritage, and everything from the names of the Jackson Civic Center to the region’s child abuse prevention program bears witness to the depths of his influence. West Tennessee—all of West Tennessee—loves Carl. And rightly so.

Most will have a degree of familiarity with Perkins’s impressive resume as a popular recording artist, and his philanthropic actives through the founding of The Exchange Club, Carl Perkins Center for the Prevention of Child Abuse. What may be less well known, is how deeply rooted the young artist was in McNairy County’s distinctive musical traditions. But that is a story, we love to tell. And it goes like this:

Born near Tiptonville in Lake County, Tennessee, Carl Perkins was deeply influenced by the sounds he absorbed in the cotton fields of the West Tennessee Delta, as well as the blues and country he heard on Mid South radio of his youth. But Lake County is, quite literally, as far as you can get from McNairy County, and still be in West Tennessee. Fortunately for us, the Perkins family would make their way south, settling first in Bemis and later in Jackson Tennessee. Carl may have left Tiptonville behind, but not the lessons he learned there. The young artist began to play around Southwest Tennessee anywhere he could find music being made. There was no shortage of venues, and the young guitarist brought with him a distinctive sound influenced by his early exposure to African American music, especially the style of “Uncle” John Westbrook, who had given him his first informal lessons on the front porch of his Lake County sharecropper’s cabin. Nobody sounded quite like Carl, and he never forgot to credit “Uncle John” as a crucial source of that difference.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, one of the best music jams in the region was staged by a Selmer business man by the name of Earl Latta in this very room. Some of the best pickers in the area beat a path to Latta’s Ford dealership for his big weekend jams. Numbered among them was an eager young Perkins. Though he was just a teenager, he was learning valuable lessons from his peers and mentors while cutting his teeth as a performer. His frequent trips to Selmer and other areas of the county put him in contact Rob Richard, Waldo Davis, Ray Presley, Charlie Cox, Francis Hendrix and other notable local players from whom he drew significant inspiration. Perhaps, most significantly, he was well known to have played with McNairy County Music Hall of Famers, Arnold English and the Dixie Hayriders, on radio shows in Jackson, Tennessee when Carl was an still an unknown and the English brothers’ stars were on the rise. Another period photo from Perkins’s autobiography shows him playing at a hardware store grand opening in the early 1950s being backed by McNairy County boys Benny Coley and Lindsey Patterson. Since McNairy County had one of the most diverse and thriving music scenes in West Tennessee, Perkins would have heard and soaked up the influence of many other local hall of famers such as Ernest Whitten and Elvis Black. This repeated and prolonged exposure to McNairy County’s rich musical traditions undoubtedly shaped Perkins’s sound in many ways.

Carl’s connection to McNairy County music doesn't end with a few period photos and a credible body of oral tradition. As unlikely as it may be, there is indisputable sonic evidence. Carl’s distinctive voice and guitar stylings can clearly be heard in an archive of recordings made at Eastview, Tennessee. Beginning in 1951, prior to his rise to stardom as a national artist on the Sun label, Perkins cut at least three sides with Stanton Littlejohn. These are widely thought to be the first documented recordings of the up and coming rocker’s career and they are remarkable in what they reveal about Carl’s earliest creative instincts. Perkins undoubtedly learned about Littlejohn’s amateur recording activity through his contact with the lengthy list of local players he collaborated with, in those years. It is believed that Carl intended to make demo recording for the purpose of shopping his music around with various national recording labels. In later interviews, Carl would confirm that he did just that during the same period he made the Eastview recordings, though he neglects to mention where the demos were cut. Littlejohn, who was inducted into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in 2013, is an odds on favorite for making those demos, as extant recordings from his collection now seem to prove. It’s probably worth pausing at this point to take a listen. Lady’s and Gentleman, this is Carl Perkins, circa 1953, recorded in McNairy County, Tennessee by Stanton Littlejohn.

How about that?

And there is more! A seminal event in Perkins’s career took place at Bethel Springs, Tennessee in 1954. Just months after Elvis Presley’s first Sun Records release “That’s Alright” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” the Hillbilly Cat, as some were calling Presley, appeared at Bethel Springs High School. Carl had heard Presley’s recordings on the radio and immediately recognized echoes of his own style. He planned to attend the concert and met Presley for the first time there. Perkins was impressed with what he heard and, after the show, the two discussed how Presley had managed to get a contract with Sun Records. Little more than a month later, Perkins auditioned at Sun and signed his own contract. In later years, Carl would recall that Bethel Springs was the place where the light finally went on for him. It was there he realized the brand of music he and Presley were pioneering appealed primarily to younger audiences. That simple insight was a game changer. He would always remember that McNairy County moment as an important turning point in his stellar career.

Just as McCartney observed there would have been no Beatles without Carl Perkins, there might have been no Carl Perkins without McNairy County. Carl drew deeply from the well of musical resources McNairy County had to offer him, and in his turn altered the course of American music history. Tonight we pay homage to Carl’s unparalleled legacy and in so doing, we bring honor to all those who helped shape his music. And, we are proud to say we are still on a first name basis with the Father of Rockabilly Music.

It is my honor to induct Carl Perkins into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in the class of 2017.

June 9, 2017

It is hardly necessary to recite the many accomplishments of an artist such as Carl Perkins who is, without a doubt, one of the most revered figures in American music history. But in case you just arrived on the planet, we’ll bring you up to speed with the briefest overview.

Perkins is widely acknowledged as the “Father of Rockabilly Music” and an authentic cultural voice of the post-war South. His effortless mixing of honky-tonk country and R&B styles helped touch off a cultural revolution that gave birth to rock ’n’ roll, forever altering the course of American culture. The list of musicians and performers who cite Perkins as a primary influence reads like a who’s who of twentieth century rock music: Paul McCartney, George Harrison, John Fogerty, Rick Nelson, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Tom Petty, Paul Simon, Ronnie Hawkins, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the list goes on and on. Sir Paul McCartney famously said in one interview, “Without Carl Perkins, there would have been no Beatles.” The list of chart topping records, music industry awards, and international acknowledgments showered on Perkins are too numerous to mention. Suffice it to say he is a Grammy Award winner, a member of the Rock ’n’ Roll and Rockabilly Halls of Fame, and he is universally respected as an architect of contemporary popular music. His song, “Blue Suede Shoes,” is now one of the most familiar tunes ever written, as well as one of the most influential in American music history. The tune’s lasting impact has been acknowledged by inclusion in the Grammy Hall of Fame, the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry, and the Rolling Stone Magazine’s “Greatest Songs of All Times.” Perhaps under appreciated as a song writer, Perkins had five (FIVE!) compositions recorded by the Beatles, and many others by artists as diverse as Patsy Cline, George Thorogood, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, Jimmy Page, Dolly Parton, the Kentucky Headhunters, and the Judds. As a musician, Carl Perkins, along with contemporary artist and friend, Chuck Berry, virtually invented what would become the blueprint for rock ’n’ roll guitar—which is to say, the very sound of popular music for more than half a century now.

Here, in West Tennessee, Carl Perkins has achieved that rare status of a one-name-sensation like Cher, Madonna, or maybe more fitting for this occasion, Elvis. To us, he is just Carl. He is undisputed favorite native son of West Tennessee music. His name is synonymous with the regions incredible musical heritage, and everything from the names of the Jackson Civic Center to the region’s child abuse prevention program bears witness to the depths of his influence. West Tennessee—all of West Tennessee—loves Carl. And rightly so.

Most will have a degree of familiarity with Perkins’s impressive resume as a popular recording artist, and his philanthropic actives through the founding of The Exchange Club, Carl Perkins Center for the Prevention of Child Abuse. What may be less well known, is how deeply rooted the young artist was in McNairy County’s distinctive musical traditions. But that is a story, we love to tell. And it goes like this:

Born near Tiptonville in Lake County, Tennessee, Carl Perkins was deeply influenced by the sounds he absorbed in the cotton fields of the West Tennessee Delta, as well as the blues and country he heard on Mid South radio of his youth. But Lake County is, quite literally, as far as you can get from McNairy County, and still be in West Tennessee. Fortunately for us, the Perkins family would make their way south, settling first in Bemis and later in Jackson Tennessee. Carl may have left Tiptonville behind, but not the lessons he learned there. The young artist began to play around Southwest Tennessee anywhere he could find music being made. There was no shortage of venues, and the young guitarist brought with him a distinctive sound influenced by his early exposure to African American music, especially the style of “Uncle” John Westbrook, who had given him his first informal lessons on the front porch of his Lake County sharecropper’s cabin. Nobody sounded quite like Carl, and he never forgot to credit “Uncle John” as a crucial source of that difference.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, one of the best music jams in the region was staged by a Selmer business man by the name of Earl Latta in this very room. Some of the best pickers in the area beat a path to Latta’s Ford dealership for his big weekend jams. Numbered among them was an eager young Perkins. Though he was just a teenager, he was learning valuable lessons from his peers and mentors while cutting his teeth as a performer. His frequent trips to Selmer and other areas of the county put him in contact Rob Richard, Waldo Davis, Ray Presley, Charlie Cox, Francis Hendrix and other notable local players from whom he drew significant inspiration. Perhaps, most significantly, he was well known to have played with McNairy County Music Hall of Famers, Arnold English and the Dixie Hayriders, on radio shows in Jackson, Tennessee when Carl was an still an unknown and the English brothers’ stars were on the rise. Another period photo from Perkins’s autobiography shows him playing at a hardware store grand opening in the early 1950s being backed by McNairy County boys Benny Coley and Lindsey Patterson. Since McNairy County had one of the most diverse and thriving music scenes in West Tennessee, Perkins would have heard and soaked up the influence of many other local hall of famers such as Ernest Whitten and Elvis Black. This repeated and prolonged exposure to McNairy County’s rich musical traditions undoubtedly shaped Perkins’s sound in many ways.

Carl’s connection to McNairy County music doesn't end with a few period photos and a credible body of oral tradition. As unlikely as it may be, there is indisputable sonic evidence. Carl’s distinctive voice and guitar stylings can clearly be heard in an archive of recordings made at Eastview, Tennessee. Beginning in 1951, prior to his rise to stardom as a national artist on the Sun label, Perkins cut at least three sides with Stanton Littlejohn. These are widely thought to be the first documented recordings of the up and coming rocker’s career and they are remarkable in what they reveal about Carl’s earliest creative instincts. Perkins undoubtedly learned about Littlejohn’s amateur recording activity through his contact with the lengthy list of local players he collaborated with, in those years. It is believed that Carl intended to make demo recording for the purpose of shopping his music around with various national recording labels. In later interviews, Carl would confirm that he did just that during the same period he made the Eastview recordings, though he neglects to mention where the demos were cut. Littlejohn, who was inducted into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in 2013, is an odds on favorite for making those demos, as extant recordings from his collection now seem to prove. It’s probably worth pausing at this point to take a listen. Lady’s and Gentleman, this is Carl Perkins, circa 1953, recorded in McNairy County, Tennessee by Stanton Littlejohn.

How about that?

And there is more! A seminal event in Perkins’s career took place at Bethel Springs, Tennessee in 1954. Just months after Elvis Presley’s first Sun Records release “That’s Alright” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” the Hillbilly Cat, as some were calling Presley, appeared at Bethel Springs High School. Carl had heard Presley’s recordings on the radio and immediately recognized echoes of his own style. He planned to attend the concert and met Presley for the first time there. Perkins was impressed with what he heard and, after the show, the two discussed how Presley had managed to get a contract with Sun Records. Little more than a month later, Perkins auditioned at Sun and signed his own contract. In later years, Carl would recall that Bethel Springs was the place where the light finally went on for him. It was there he realized the brand of music he and Presley were pioneering appealed primarily to younger audiences. That simple insight was a game changer. He would always remember that McNairy County moment as an important turning point in his stellar career.

Just as McCartney observed there would have been no Beatles without Carl Perkins, there might have been no Carl Perkins without McNairy County. Carl drew deeply from the well of musical resources McNairy County had to offer him, and in his turn altered the course of American music history. Tonight we pay homage to Carl’s unparalleled legacy and in so doing, we bring honor to all those who helped shape his music. And, we are proud to say we are still on a first name basis with the Father of Rockabilly Music.

It is my honor to induct Carl Perkins into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in the class of 2017.