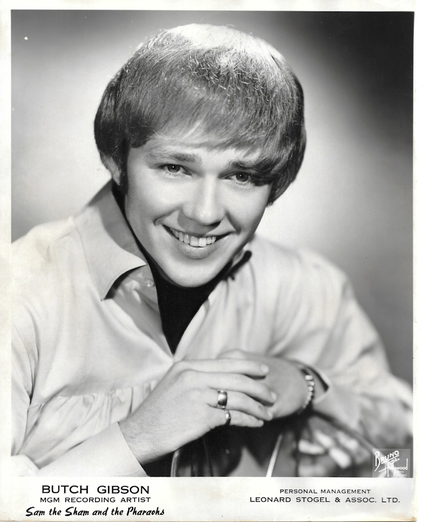

Paul "Butch" Gibson

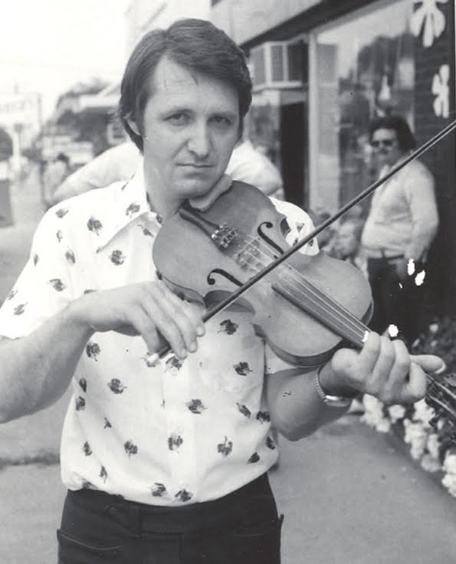

Original Saxophonist, Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs

As read by Robert Lee, Arts in McNairy Boardmember

June 8, 2018

In January 1964, Life Magazine reported it this way: “In 1776 England lost her American colonies. Last week, the Beatles took them back.” It was a bloodless coup which would later be called “The British Invasion,” and the Beatles were just the tip of the iceberg. Between 1963 and 1967 a steady stream of British acts would dominate the American popular music charts. The unparalleled success of acts like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Animals, The Who, The Yardbirds, The Hollies, Cream, The Kinks and a host of other British bands, would make an indelible mark on music history. The big bang of rock ’n’ roll had originated right here in our own backyard under the influence of R&B inspired country boys like Perkins and Presley, hopped the Atlantic, and came roaring back in force with a refreshed and reenergized sound that sparked the imagination of America’s youth, not to mention the rest of the world. It made culture observers and music critics wonder out loud if the heyday of American rock ’n’ roll music had finally come to its bitter end.

But Memphis wasn’t dead yet. Amid the disorienting chaos of the British Invasion, a new sound emerged from the storied studios of Memphis, Tennessee. A little known group with a Mexican-American bandleader went into Sam C. Phillips Recording Studio, the successor of Sun Records, and cut a single that was released in 1964 by the small Memphis-based XL Label. An immediate sensation, the single was picked up by MGM, and shot to the top of the charts. That record was “Wooly Bully” and the band was Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs. Among other things, it served notice that American music would not go quietly into the night; our creative energies were not yet depleted; we still had something to say musically.

“Wooly Bully” sold 3 million copies internationally and spent 18 weeks on the Hot 100 chart in 1965, at the height of the British Invasion. It was named Billboard’s Number One Record of the Year and propelled Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs into stratospheric success. “Wooly Bully” would become one of the most recognizable songs of the 1960s, covered and recorded by countless other bands, and featured on dozens of movie soundtracks from Fast Times at Ridgemont High, to Full Metal Jacket, to Mr. Holland’s Opus.

This brief history is probably not news to most people, but what has not yet been fully acknowledged is the role one McNairy County native played in the success of “Wooly Bully” and subsequent hits by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs. A Google search for “best rock ’n’ roll sax solos,” or the equivalent, invariably turns up “Wooly Bully” on multiple lists ranking the most influential saxophone solos of the rock era. It’s undeniable that the sax performance on that record invests the simple tune with an infectious energy and if the solo verse doesn’t make you want to get up on your feet and dance, you need to check your pulse. That little piece of musical artistry was created and performed by a kid from Adamsville, Tennessee. A kid named Butch Gibson.

Paul “Butch” Gibson grew up on North Maple Street, a few blocks from downtown Adamsville, where his parents Dink and Mary Francis Gibson were woven into the fabric of the civic and business community running the local hardware store. His mother was a pianist who played for family gatherings and church choir; the Gibson home was always full of music. The big band swing that his parents favored was always on the radio or turntable at home, and this will probably account, in part, for Butch's early interest in saxophone. But the spirited gospel music he heard as a youth also comes through loud and clear in the soulful style he lent to the music he performed with various R&B and rock ’n’ roll bands over the years.

Butch’s earliest musical memories involve his parents investing in piano lessons which didn’t quite take. He preferred noodling around on the keys to the formality of music lessons and the limits of the written page didn’t make much sense to him. So he learned to play piano by ear. A pivotal musical moment came early for him when, at five years old, his mother dressed him up in a cowboy outfit and signed him up to sing in the annual harvest festival. He performed “Ghost Riders in the Sky.” When he unholstered his six shooters at the end of the song and fired off an eye-opening round of caps, the crowd went wild. He got a standing ovation and Butch was hooked.

A few years later when Adamsville was resurrecting the school band program under the direction of a Oscar Ozols, Butch’s parents insisted that he give it a try. Of course, his interest and aptitude for music had not escaped their attention and he was excited about the opportunity. Butch says he believes that musicians don’t always choose their instruments, sometimes the instruments choose them, and that’s exactly what happened that fateful day he went to see what school band was all about. The minute he walked through the door of the auditorium, a gleaming alto saxophone in a green, velvet-lined case called to him. That alto would become his primary instrument and he still owns it today, occasionally dusting it off and playing a little for his own enjoyment. He would later acquire the tenor sax he played on "Wooly Bully", and refine his skills on keyboards. Adding guitar and bass to the list of instruments he could competently play, made him a versatile choice for a variety of musical situations and foreshadowed his success on the Memphis music scene.

At only 14 years of age, Butch joined his first band, the Superchargers, a group of Savannah boys including Larry Roser on drums and Larry “Boo” Rogers on keyboards. They had to pick Butch up for gigs and rehearsals since he was too young to drive. Shortly thereafter he was off to boarding school where he formed his own band called The Combo. The new environment exposed Butch to different musical influences and allowed him to further expand his musical skills and tastes. Several of his classmates and musical collaborators brought strange and wonderful new sounds to his attention. The records his deep-fried Louisiana friends spun echoed some of the big band jazz styles he grew up loving but infused the music with the passion of gospel, and the pain of the blues. Slim Harpo, B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Bobby Blue Bland, and James Brown became some of his primary influences during this time and he naturally gravitated towards R&B from that time on.

When Butch landed in Memphis for college, he soon hooked up with Joe Davis and the Allstars, a band fronted by the dynamic vocal trio, the Avantis. The group was a popular regional act, touring and performing throughout the Mid-South. The Avanti’s cut “Keep on Dancing” at American Studios and the tune became a big hit for the Gentrys. The groups lead singer, Billy Young, later joined the popular vocal group The Ovations. But Joe Davis knew Butch was not entirely happy with the style of music they were making together—he knew Butch loved R&B. Joe arranged for them to go check out a new R&B act which was beginning to make some waves on the Memphis music scene.

The flamboyant Domingo “Sam” Samudio was a recent transplant from Dallas, Texas, by way of Louisiana. He had come to Memphis with a group called the Nightriders which had disbanded just months after arrival, stranding Sam without a band. He had quickly recruited a couple of new players and renamed the band Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs. It was about this time that Butch showed up to check out the new R&B outfit. He sat in with the band who didn’t yet have a sax player, and they hired him on the spot.

Butch was able to step seamlessly into the role, primarily playing sax but also doubling on organ in live performances so Sam could get out front and entertain the crowd. He could, in fact, play every instrument in the band except drums, which came in handy on the road and in the studio.

Through most of 1963 and 64 Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs were playing club dates in and around Memphis, trying out new material on live audience and honing their sound. It was an incredible mix of talent. The Pharaohs combined the gritty sound of Memphis blues and rock, with Sam’s Tex-Mex conjunto roots and Butch’s flare for R&B. They quickly became one of the hottest bands in Memphis. When they went into the studio to cut a single, the recording techs suggested they do the tune that was most popular with their nightclub following. Hully Gully, a basic pop tune by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, always got a good response, but you can’t just record someone else’s material. They started with the same simple 12 bar blues progression for a foundation, rewrote the lyrics, and replaced “Hully Gully” with the name of Sam’s cat, Wooly Bully. Of course, they brought their own unique sound to bear on the tune too. Sam, counted them off, "Uno! Dos! One, two, tres, cuatro!” and the Pharaohs stepped into rock ’n’ roll history. They did three takes of “Wooly Bully” that day, but it was the very first one that made it to the final record. Sam didn’t like the count off on the record, but the sound engineers instincts were to leave it as it was. And a good thing too, it’s one of the quirks that makes that track so memorable.

Butch recalls that before Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs went into the studio to cut “Wooly Bully” they were barely scraping by playing for a few dozen people nightly in Memphis clubs. A month later they were playing a sold out coliseum in Atlanta with the Beach Boys. It was the beginning of a meteoric rise that would take Sam, Butch and the Pharaohs from Alaska to Florida, from Maine to Southern California and all points in between. Hitting the road in support of a top 10 record would mean touring Europe and playing places like Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl. It would mean playing in front of 50,000 people at a Seattle arena. It would mean appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show, Hullabaloo and Dick Clark’s Cavalcade of Stars. It would mean touring and sharing the stage with the likes of Ike and Tina Turner, The Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, and one of Butch’s musical heroes, James Brown, just to name a few of the more notable artists. When asked what that must have been like, Butch simply said, “We had a great time.” I’ll bet they did!

After recording two albums and charting several more hits with Sam and the Pharaohs, Butch drifted away from the music business but continued to play and sing on occasion. His last professional experience in the music industry was with a gospel group called the Confederates who worked for several years around the Mid South and opened for the Blackwood Brothers at Memphis’s famed Ellis Auditorium.

These days Butch lives in Foley Alabama where he is currently finishing up doctoral studies in Education. It will be his 5th degree. He is retired from a successful career with DuPont and found yet another calling as an advocate for the unique educational needs of children living in poverty. He successfully passed his love of music on to his children and grandchildren. One of his daughters is a band director, his grandson plays drums for a country band, and one granddaughter is a multi-instrumentalist and first chair violinist in her local pops philharmonic orchestra.

Butch still enjoys music and still plays it occasionally. He says he believes all music has dignity and value and should be respected on its own terms. That pretty succinctly describes the mission of the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame, and we are delighted to have the opportunity to share some of Butch’s incredible musical story with you tonight. It’s a long way from Adamsville, Tennessee to the Hollywood Bowl and Butch has made the trip in style. He speaks with great affection about his McNairy County roots and credits those who mentored him in music with his success. And in turn, we feel a sense of pride that a man of such grace and humility would be an ambassador for our community and our cultural traditions in the highest reaches of the music industry. It’s quite an honor for us to know that one of the most iconic saxophone performances of the rock ’n’ roll era has its roots in the band program of a local public school. And that, folks, is a lesson in the value of music education.

In summing up his biography for this occasion, Butch concluded with a favorite quote from Sam the Sham. He says Sam used to close out all of their shows by saying a few heartfelt words of wisdom to the audience. So, perhaps it is fitting tonight that we wrap Butch’s induction up with the words of Domingo Samudio, who offers this sage advice to one and all:

That old clock on the wall done caught up with us all, and we’re going to roll out of here like a hole in a donut.

And remember, you’ve got to be yourself, or else you’ll wind up by yourself.

And like the old gypsy woman told me, life is short and talk is cheap, don’t make promises you can’t keep.

And you know I love you baby, cause if I don’t love you, grits ain’t groceries, eggs ain’t poultry, and The Mona Lisa was a man.

That about says it all. It is my distinct honor to induct Paul “Butch” Gibson into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in the class of 2018.

June 8, 2018

In January 1964, Life Magazine reported it this way: “In 1776 England lost her American colonies. Last week, the Beatles took them back.” It was a bloodless coup which would later be called “The British Invasion,” and the Beatles were just the tip of the iceberg. Between 1963 and 1967 a steady stream of British acts would dominate the American popular music charts. The unparalleled success of acts like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Animals, The Who, The Yardbirds, The Hollies, Cream, The Kinks and a host of other British bands, would make an indelible mark on music history. The big bang of rock ’n’ roll had originated right here in our own backyard under the influence of R&B inspired country boys like Perkins and Presley, hopped the Atlantic, and came roaring back in force with a refreshed and reenergized sound that sparked the imagination of America’s youth, not to mention the rest of the world. It made culture observers and music critics wonder out loud if the heyday of American rock ’n’ roll music had finally come to its bitter end.

But Memphis wasn’t dead yet. Amid the disorienting chaos of the British Invasion, a new sound emerged from the storied studios of Memphis, Tennessee. A little known group with a Mexican-American bandleader went into Sam C. Phillips Recording Studio, the successor of Sun Records, and cut a single that was released in 1964 by the small Memphis-based XL Label. An immediate sensation, the single was picked up by MGM, and shot to the top of the charts. That record was “Wooly Bully” and the band was Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs. Among other things, it served notice that American music would not go quietly into the night; our creative energies were not yet depleted; we still had something to say musically.

“Wooly Bully” sold 3 million copies internationally and spent 18 weeks on the Hot 100 chart in 1965, at the height of the British Invasion. It was named Billboard’s Number One Record of the Year and propelled Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs into stratospheric success. “Wooly Bully” would become one of the most recognizable songs of the 1960s, covered and recorded by countless other bands, and featured on dozens of movie soundtracks from Fast Times at Ridgemont High, to Full Metal Jacket, to Mr. Holland’s Opus.

This brief history is probably not news to most people, but what has not yet been fully acknowledged is the role one McNairy County native played in the success of “Wooly Bully” and subsequent hits by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs. A Google search for “best rock ’n’ roll sax solos,” or the equivalent, invariably turns up “Wooly Bully” on multiple lists ranking the most influential saxophone solos of the rock era. It’s undeniable that the sax performance on that record invests the simple tune with an infectious energy and if the solo verse doesn’t make you want to get up on your feet and dance, you need to check your pulse. That little piece of musical artistry was created and performed by a kid from Adamsville, Tennessee. A kid named Butch Gibson.

Paul “Butch” Gibson grew up on North Maple Street, a few blocks from downtown Adamsville, where his parents Dink and Mary Francis Gibson were woven into the fabric of the civic and business community running the local hardware store. His mother was a pianist who played for family gatherings and church choir; the Gibson home was always full of music. The big band swing that his parents favored was always on the radio or turntable at home, and this will probably account, in part, for Butch's early interest in saxophone. But the spirited gospel music he heard as a youth also comes through loud and clear in the soulful style he lent to the music he performed with various R&B and rock ’n’ roll bands over the years.

Butch’s earliest musical memories involve his parents investing in piano lessons which didn’t quite take. He preferred noodling around on the keys to the formality of music lessons and the limits of the written page didn’t make much sense to him. So he learned to play piano by ear. A pivotal musical moment came early for him when, at five years old, his mother dressed him up in a cowboy outfit and signed him up to sing in the annual harvest festival. He performed “Ghost Riders in the Sky.” When he unholstered his six shooters at the end of the song and fired off an eye-opening round of caps, the crowd went wild. He got a standing ovation and Butch was hooked.

A few years later when Adamsville was resurrecting the school band program under the direction of a Oscar Ozols, Butch’s parents insisted that he give it a try. Of course, his interest and aptitude for music had not escaped their attention and he was excited about the opportunity. Butch says he believes that musicians don’t always choose their instruments, sometimes the instruments choose them, and that’s exactly what happened that fateful day he went to see what school band was all about. The minute he walked through the door of the auditorium, a gleaming alto saxophone in a green, velvet-lined case called to him. That alto would become his primary instrument and he still owns it today, occasionally dusting it off and playing a little for his own enjoyment. He would later acquire the tenor sax he played on "Wooly Bully", and refine his skills on keyboards. Adding guitar and bass to the list of instruments he could competently play, made him a versatile choice for a variety of musical situations and foreshadowed his success on the Memphis music scene.

At only 14 years of age, Butch joined his first band, the Superchargers, a group of Savannah boys including Larry Roser on drums and Larry “Boo” Rogers on keyboards. They had to pick Butch up for gigs and rehearsals since he was too young to drive. Shortly thereafter he was off to boarding school where he formed his own band called The Combo. The new environment exposed Butch to different musical influences and allowed him to further expand his musical skills and tastes. Several of his classmates and musical collaborators brought strange and wonderful new sounds to his attention. The records his deep-fried Louisiana friends spun echoed some of the big band jazz styles he grew up loving but infused the music with the passion of gospel, and the pain of the blues. Slim Harpo, B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Bobby Blue Bland, and James Brown became some of his primary influences during this time and he naturally gravitated towards R&B from that time on.

When Butch landed in Memphis for college, he soon hooked up with Joe Davis and the Allstars, a band fronted by the dynamic vocal trio, the Avantis. The group was a popular regional act, touring and performing throughout the Mid-South. The Avanti’s cut “Keep on Dancing” at American Studios and the tune became a big hit for the Gentrys. The groups lead singer, Billy Young, later joined the popular vocal group The Ovations. But Joe Davis knew Butch was not entirely happy with the style of music they were making together—he knew Butch loved R&B. Joe arranged for them to go check out a new R&B act which was beginning to make some waves on the Memphis music scene.

The flamboyant Domingo “Sam” Samudio was a recent transplant from Dallas, Texas, by way of Louisiana. He had come to Memphis with a group called the Nightriders which had disbanded just months after arrival, stranding Sam without a band. He had quickly recruited a couple of new players and renamed the band Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs. It was about this time that Butch showed up to check out the new R&B outfit. He sat in with the band who didn’t yet have a sax player, and they hired him on the spot.

Butch was able to step seamlessly into the role, primarily playing sax but also doubling on organ in live performances so Sam could get out front and entertain the crowd. He could, in fact, play every instrument in the band except drums, which came in handy on the road and in the studio.

Through most of 1963 and 64 Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs were playing club dates in and around Memphis, trying out new material on live audience and honing their sound. It was an incredible mix of talent. The Pharaohs combined the gritty sound of Memphis blues and rock, with Sam’s Tex-Mex conjunto roots and Butch’s flare for R&B. They quickly became one of the hottest bands in Memphis. When they went into the studio to cut a single, the recording techs suggested they do the tune that was most popular with their nightclub following. Hully Gully, a basic pop tune by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, always got a good response, but you can’t just record someone else’s material. They started with the same simple 12 bar blues progression for a foundation, rewrote the lyrics, and replaced “Hully Gully” with the name of Sam’s cat, Wooly Bully. Of course, they brought their own unique sound to bear on the tune too. Sam, counted them off, "Uno! Dos! One, two, tres, cuatro!” and the Pharaohs stepped into rock ’n’ roll history. They did three takes of “Wooly Bully” that day, but it was the very first one that made it to the final record. Sam didn’t like the count off on the record, but the sound engineers instincts were to leave it as it was. And a good thing too, it’s one of the quirks that makes that track so memorable.

Butch recalls that before Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs went into the studio to cut “Wooly Bully” they were barely scraping by playing for a few dozen people nightly in Memphis clubs. A month later they were playing a sold out coliseum in Atlanta with the Beach Boys. It was the beginning of a meteoric rise that would take Sam, Butch and the Pharaohs from Alaska to Florida, from Maine to Southern California and all points in between. Hitting the road in support of a top 10 record would mean touring Europe and playing places like Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl. It would mean playing in front of 50,000 people at a Seattle arena. It would mean appearing on the Ed Sullivan Show, Hullabaloo and Dick Clark’s Cavalcade of Stars. It would mean touring and sharing the stage with the likes of Ike and Tina Turner, The Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, and one of Butch’s musical heroes, James Brown, just to name a few of the more notable artists. When asked what that must have been like, Butch simply said, “We had a great time.” I’ll bet they did!

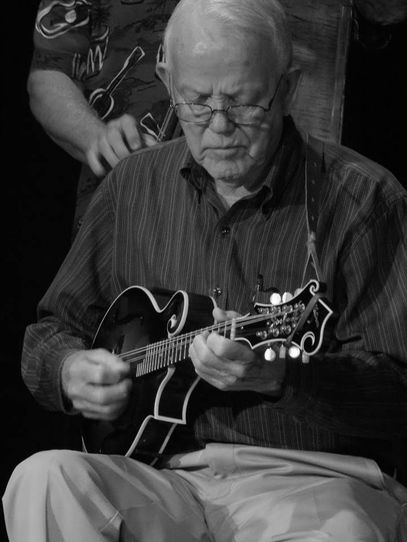

After recording two albums and charting several more hits with Sam and the Pharaohs, Butch drifted away from the music business but continued to play and sing on occasion. His last professional experience in the music industry was with a gospel group called the Confederates who worked for several years around the Mid South and opened for the Blackwood Brothers at Memphis’s famed Ellis Auditorium.

These days Butch lives in Foley Alabama where he is currently finishing up doctoral studies in Education. It will be his 5th degree. He is retired from a successful career with DuPont and found yet another calling as an advocate for the unique educational needs of children living in poverty. He successfully passed his love of music on to his children and grandchildren. One of his daughters is a band director, his grandson plays drums for a country band, and one granddaughter is a multi-instrumentalist and first chair violinist in her local pops philharmonic orchestra.

Butch still enjoys music and still plays it occasionally. He says he believes all music has dignity and value and should be respected on its own terms. That pretty succinctly describes the mission of the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame, and we are delighted to have the opportunity to share some of Butch’s incredible musical story with you tonight. It’s a long way from Adamsville, Tennessee to the Hollywood Bowl and Butch has made the trip in style. He speaks with great affection about his McNairy County roots and credits those who mentored him in music with his success. And in turn, we feel a sense of pride that a man of such grace and humility would be an ambassador for our community and our cultural traditions in the highest reaches of the music industry. It’s quite an honor for us to know that one of the most iconic saxophone performances of the rock ’n’ roll era has its roots in the band program of a local public school. And that, folks, is a lesson in the value of music education.

In summing up his biography for this occasion, Butch concluded with a favorite quote from Sam the Sham. He says Sam used to close out all of their shows by saying a few heartfelt words of wisdom to the audience. So, perhaps it is fitting tonight that we wrap Butch’s induction up with the words of Domingo Samudio, who offers this sage advice to one and all:

That old clock on the wall done caught up with us all, and we’re going to roll out of here like a hole in a donut.

And remember, you’ve got to be yourself, or else you’ll wind up by yourself.

And like the old gypsy woman told me, life is short and talk is cheap, don’t make promises you can’t keep.

And you know I love you baby, cause if I don’t love you, grits ain’t groceries, eggs ain’t poultry, and The Mona Lisa was a man.

That about says it all. It is my distinct honor to induct Paul “Butch” Gibson into the McNairy County Music Hall of Fame in the class of 2018.